Trustees' Garden has always been an integral part of the history of Savannah.

Founded by James Oglethorpe in 1734, Trustees’ Garden served as a testing grounds to determine what crops would flourish in this new land. Given its elevation and proximity to the river, the site was a natural choice for military defense in times of war and peace.

Following an influx of Irish immigration, this campus housed the nation’s largest Iron Works. William Kehoe, acquired Phoenix Architectural Works and, upon renaming it after himself in 1883, expanded it to include a marine-engineering shop and facilities to produce structural steel, brass fittings, and a range of iron goods: sugar mills and boilers, manhole covers, and more.

Additional uses for this site include the Savannah Gas Light Company, which converted coal to gas and housed a demo kitchen known as the Wonderflame Room.

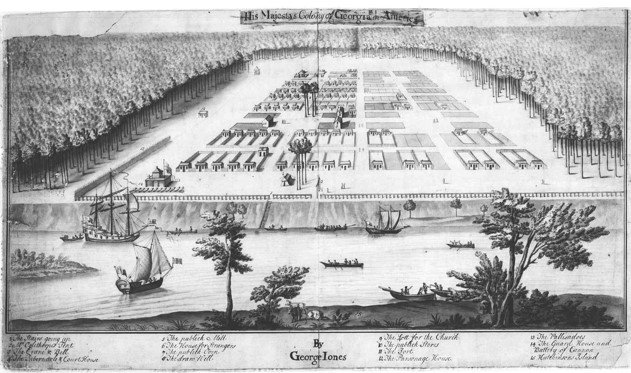

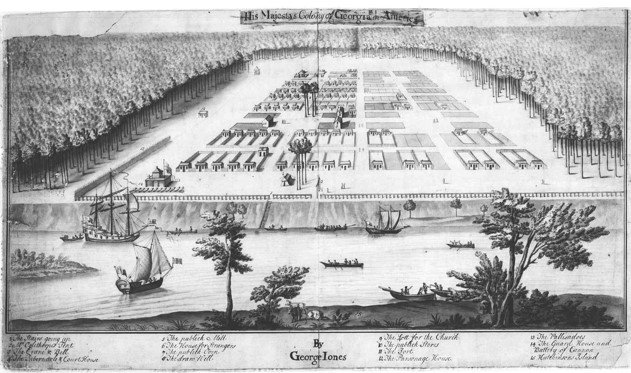

1734

The Founding of Trustees’ Garden

Chartered by King Charles, in 1732 and settled in 1733, Georgia colony and the town of Savannah where to host the first Crown-sanctioned experimental garden in the New World. Known locally as the Trustees’ Garden, a ten-acre plot of land on the bluff along the Savannah River.

Surveyed the first year of settlement, the garden was not planted until the growing season in 1734. Still, it was impressive enough the next year for visitor and writer Francis Moore to write, “…all kinds of fruit trees usual in England, such as apples, pears, etc. In another quarter are olives, figs, vines, pomegranates and such fruits that are natural to the warmest parts of Europe… In the warmest part of the garden, there was a collection of West India plants and trees, some coffee, some cocoa-nuts, cotton, Palma Christi, and several West India physical plants….” Peaches and cotton were among the tested crops. They both still grow well in Georgia’s soil and climate. Trustees’ Garden was the first location in North America where cotton was grown for commercial use.

1759

The Forts at Trustees’ Garden

From the beginning of the colony, Trustees' Garden was utilized as a prime defensive military site. A battery of cannon was placed here at the founding. Later in 1739, Fort Oglethorpe was built of log construction. In 1759 the ruins were rebuilt to create Fort Halifax which lasted into the American Revolution.

During that time, it was the scene of protest by the Sons of Liberty, when Parliament passed a stamp tax on several trade goods. In the American Revolution an American fort was created on the site and is known both as Fort Charlotte and Fort Savannah.

Later the British captured Savannah and constructed cannon batteries on the site that experienced fire from American and French forces in 1779. After the British victory, a new fort named for the British commander of the city was built and dubbed Fort Prevost.

At the war’s end the fort was renamed Fort Wayne after Revolutionary General “Mad” Anthony Wayne and rebuilt into a crescent shape. During the Civil War, U.S. General William T. Sherman’s army captured the city in 1865 and a protective wall crossed the garden and rimmed the city in case of a Rebel counter strike.

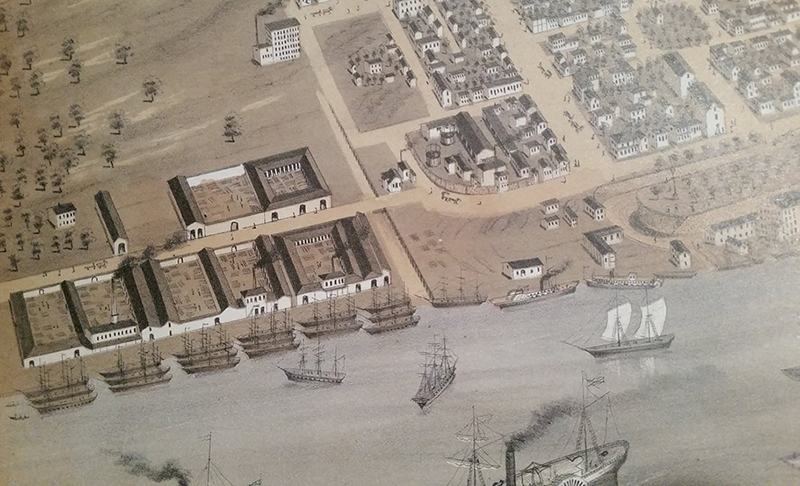

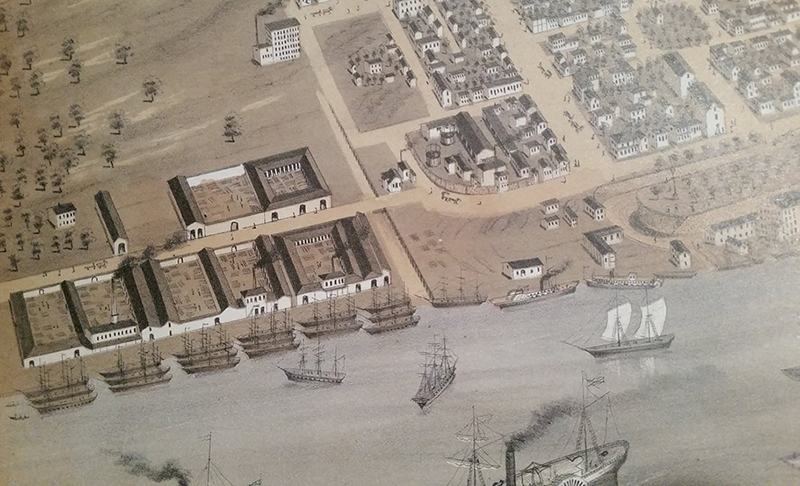

1860

Neighborhood and Culture

In the mid-twentieth century, Troup and Washington Squares competed to “hook boxes,” each hoping to outdo the other’s New Year’s Eve bonfire. This was but one distinctive tradition of Old Fort, the working-class neighborhood, east of the Historic District, that supplied labor for Kehoe’s Iron Works.

The Kehoes were among the many Irish immigrants who settled alongside a substantial African-American population in Old Fort, named after the former Fort Wayne. Irish dimensions of the precinct included the Arctics, a baseball team of the 1870s.

An Irish militia, the Jasper Greens, sometimes used Washington Square for its annual salute to America’s first President. Local fire companies of note were the Irish No. 9 of Washington Square and the African-American No. 1 of Columbia Square, where, at his financial prime, William Kehoe constructed two mansions.

Before the Civil War, black slave families enjoyed relative autonomy in their own dwellings in Old Fort. Some residents traced their roots to the Gullahs and Geechees: Africans enslaved on the offshore Sea Islands. In 1874, to minister to freed slaves, French monks established in Old Fort the “mother church,” St. Benedict the Moor, for Georgia’s black Catholics.

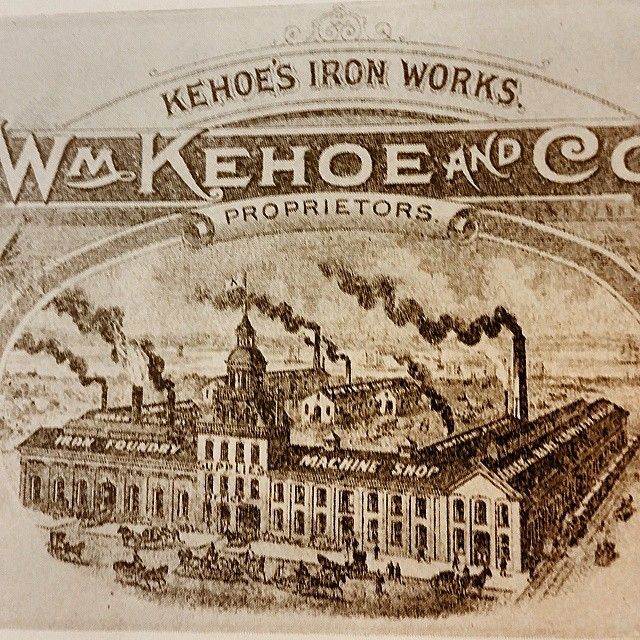

1883

Man of Iron: The William Kehoe Era

According to the February 1916 issue of Iron Tradesman, Kehoe’s Iron Works stretched from this spot to the river, constituting “the largest and best equipped plant south of Newport News [Virginia].” Its proprietor, William Kehoe, had acquired Phoenix Architectural Works from the Monahan family, and, upon renaming it after himself in 1883, had expanded it significantly. In addition to a marine-engineering shop, it featured facilities to produce structural steel, brass fittings, and a range of iron goods: sugar mills and boilers, manhole covers, and more.

Kehoe’s success allowed him to cultivate other business interests—for example, he co-founded the Chatham Savings and Loan Company. One obituary underscored his being “an originator of the Tybee Railroad,” holding “script No. 1 in recognition of his pioneering work.” It also noted his charitable service to Savannah and support of Irish causes.

Kehoe was an Irish immigrant. Evidence points to his arriving in Savannah at aged nine with his mother, father, and siblings, on February 24, 1852, aboard the barque Brothers ship: a direct voyage from his home county town, Wexford Ireland. Forward motion certainly characterized Kehoe, one of Savannah’s “most widely known and beloved citizens.”

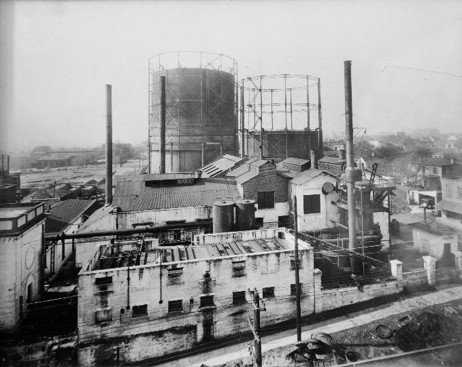

1848

Savannah Gas Light & Modern Era

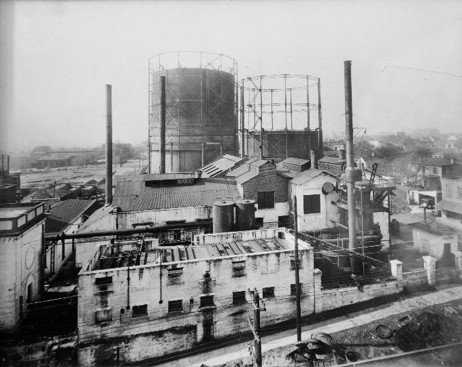

Production of gas from coal commenced on this site in 1848 with the establishment of the Savannah Gas Light Company where a century later, it handled storage capacity of up to 2 million cubic foot tanks. When the Kehoe Iron Works dissolved due to the Great Depression, the Gas Company added that plant to its existing facility. In 1946, the campus included a demo “home service kitchen and auditorium” called the Wonderflame Room.

A Gas Company amenity, the Room sought to ensure a “better diet” by advancing “new knowledge.” Today, the restored Kehoe Iron Works complex contains a state-of-the-art demonstration kitchen, dedicated to learning nutritious cooking for a healthy lifestyle.

Also in the mid-1940s, Mary Hillyer pioneered preservation of historic, but condemned buildings in Trustees’ Garden. Her contributions ensured a successful effort to save near-ruined homesteads and foster a “Village” community – a tradition that continues today.

2003

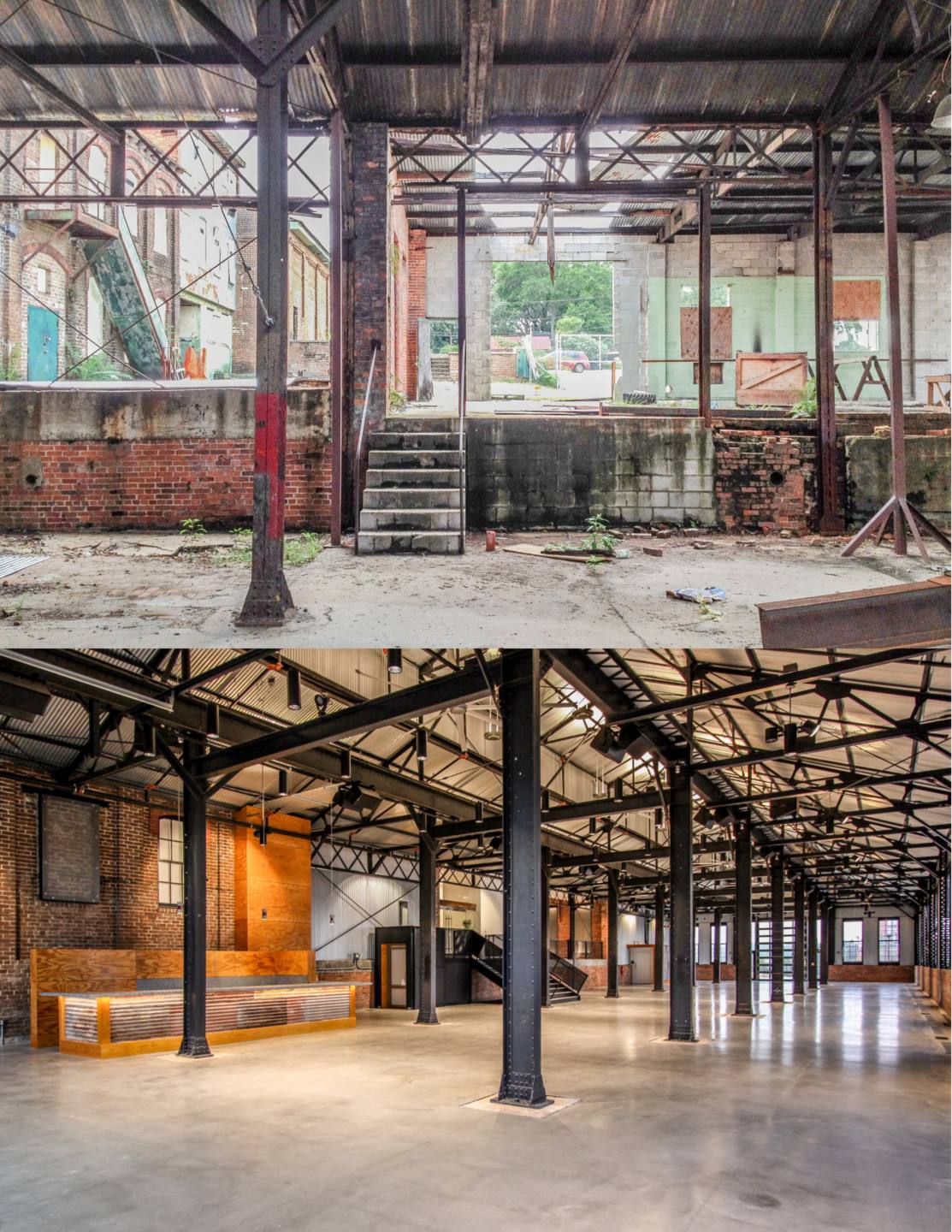

“If These Grounds Could Talk”: Charles H. Morris Restoration

In 2003, Charles H. Morris was given the opportunity to purchase the last large parcel of land in the Savannah National Historic Landmark District which encompasses 7 acres and is known as The Trustees’ Garden. Having previously restored the over 200-year-old Oliver Sturges House at 27 Abercorn Street and repurposing it for his Morris Multimedia headquarters in 1972, restoration is in his blood and preservation in his heart as a caretaker of this historically important region.

“It has always been important to me to first understand the historical context before starting a restoration project because if these grounds could talk, what a story they could tell.” – C.H. Morris

With a vision of creating a series of multi-use event spaces focused on the arts, culture, and wellness while giving reverence to the site and structures’ history, Charles Morris commissioned the restoration of numerous buildings on site - from the Morris Center atop the bluff, to the Kehoe Iron Works and the Kehoe Smithy buildings in the southeast corner. Trustees’ Garden has gone back to its roots, becoming a celebration of history and the events that now intermingle within.